Disease factsheet about poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, also known as polio or infantile paralysis, is a vaccine-preventable systemic viral infection affecting the motor neurons of the central nervous system (CNS). Historically, it has been a major cause of mortality, acute paralysis and lifelong disabilities, but large scale immunisation programmes have eliminated polio from most areas of the world. The disease is now confined to a few endemic areas and attempts are being made to globally eradicate the wild polio virus (WPV). The last WPV infection in Europe was in 1998 and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the European Region polio-free in 2002. On 5 May 2014, WHO declared the international spread of wild poliovirus in 2014 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) following the confirmed circulation of wild poliovirus in several countries and the documented exportation of wild poliovirus to other countries. Since then the international spread of polio remained a PHEIC.

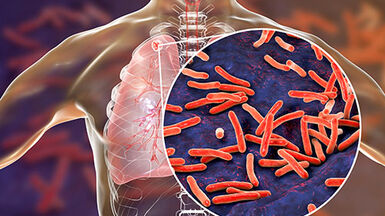

The pathogen

- Polioviruses are small single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the Enterovirus subgroup of the family Picornaviridae. Humans are the only reservoir for polio virus.

- There are three distinct serotypes of wild polio virus (WPV), types 1, 2 and 3, and infection or immunisation with one serotype does not induce immunity against the other two serotypes.

- Poliovirus type 1 has historically been the predominant cause of poliomyelitis worldwide and continues to be transmitted in endemic areas. Transmission of both WPV2 and WPV3 have been successfully interrupted globally and cases were last reported in 1999 and 2012, respectively.

- Oral polio vaccine (OPV) is produced from live attenuated WPV. On very rare occasions, if a population is seriously under-immunised, the virus can transform into pathogenic strains, known as vaccine derived poliomyelitis virus (VDPV), and circulate in the community. These viruses are called circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV).

Clinical features and sequelae

- Poliovirus infections can lead to a spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from subclinical infection to paralysis and death. The majority of poliovirus infections are asymptomatic; up to 70% of infected individuals experience no symptoms and about 25% experience mild symptoms.

- Paralytic poliomyelitis occurs in less than 1% of all infections. The disease is traditionally classified into spinal, bulbar and bulbospinal types, depending on the site of the affected motor neurons.

- Spinal poliomyelitis starts with symptoms of meningitis, followed by severe myalgia and localised sensory (hyperaesthesia, paraesthesia) and motor (spasms, fasciculations) symptoms. After one to two days, weakness and paralysis sets in.

- The weakness is classically an asymmetrical, flaccid paralysis that peaks at 48 hours after onset. This is classified as an acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). Proximal muscle groups are affected more than distal groups. Any combination of limbs may be paralysed, although lower limbs are predominantly affected.

- Bulbar poliomyelitis is a serious form of the disease resulting from paralysis of the muscles innervated by the cranial nerves, and this can lead to dysphagia, nasal speech, pooling of secretions and dyspnoea. In rare instances polio can present as encephalitis, clinically indistinguishable from other causes of viral encephalitis.

- The mortality rate for acute paralytic polio ranges from 5–15%.

- The paralysis can progress for up to one week. Permanent weakness is observed in two-thirds of patients with paralytic poliomyelitis. After 30 days, most of the reversible damage will have disappeared, and some return of function can still be expected for up to nine months.

- Post-polio syndrome is a poorly understood condition, characterised by the onset of fatigue, muscle weakness and wasting in patients who have recovered from paralytic polio. It can start several years after the acute disease. Post-polio syndrome is not an infectious disease and further discussion of the condition is beyond the scope of this factsheet. Current European consensus guidelines on diagnosis and management of post-polio syndrome are available from the European Federation of Neurological Societies.

Epidemiology

- In the pre-vaccine era, virtually all children were infected with polio virus early in life.

- Immunisation with oral polio vaccines (OPV) and inactivated polio vaccines (IPV) started towards the end of the 1950s and has significantly reduced the incidence of poliomyelitis.

- Since the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched in 1988 to eradicate all polio viruses, the global incidence has decreased by over 99% from an estimated 350 000 in 1988 in more than 125 endemic countries to 140 cases reported in two countries in 2020.

- Of the three wild poliovirus serotypes only WPV1 remains. WPV2 was declared eradicated in September 2015, with the last case detected in India in 1999. WPV3 was last detected in November 2012 in Nigeria and was declared eradicated in October 2019.

- In 1994, the WHO Region of the Americas was certified polio-free, followed by the WHO Western Pacific Region in 2000, the WHO European Region in 2002 and the WHO South-East Asia Region in 2014. In August 2020, the WHO African Region was declared free of wild poliovirus after four years with no new cases reported.

- Outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV) are rare, but the number of cases is increasing due to under-immunised populations.

- Data on poliomyelitis surveillance and disease incidence are reported in ECDC’s Annual Epidemiological Report on Communicable Diseases in Europe.

- An interactive map showing worldwide polioviruses cases, regularly updated by ECDC, is available. More information can be found on the GPEI website.

- See also the EU case definition of paralytic poliomyelitis, for the purposes of reporting communicable diseases to the community network.

Transmission

- Humans are the only known reservoir for polio virus.

- The virus is transmitted via droplets or aerosols from the throat and by faecal contamination of hands, utensils, food and water. The majority of transmissions occur via person-to-person contact or the faeco-oral route, although the oro-oral route is also possible.

- The following factors have been identified as contributing to continued polio transmission: high population density; poor health service infrastructure; poor sanitation; high incidence of diarrhoeal diseases; and low oral polio vaccine coverage.

- The incubation period is approximately 7−10 days (range 4–35 days) and about 25% of infected individuals develop mild clinical symptoms including fever, headache and sore throat.

- Infected persons are most infectious from 7−10 days before and after the onset of symptoms. However, poliovirus is excreted in the stools for up to six weeks.

- In rare cases immunodeficient patients can become asymptomatic chronic carriers of WPV and VDPV.

- Poliovirus can survive at room temperature for a few weeks. Soil, sewage and infected water have been shown to harbour the virus.

- All unimmunised persons are susceptible to the infection. Infants in the first six months may have some protection from passively transferred maternal immunity. Children under five years are at highest risk of contracting the infection.

- Poliovirus is highly infectious, with sero-conversion rates of 90–100% among household contacts.

Prevention

- Provision of clean water, improved hygienic practices and sanitation are important for reducing the risk of transmission in endemic countries.

- Immunisation is the cornerstone of polio eradication. Two types of vaccine are available: an inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) and a live attenuated oral polio vaccine (OPV).

- In the past, oral polio vaccine was the predominant vaccine in global campaigns and this is still used in endemic areas. It has the advantages of inducing both humoral and intestinal immunity. The cost of OPV is very low and the oral administration facilitates rapid mass vaccination. The disadvantage is the slight risk of vaccine associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP), which occurs in about four out of every 1 000 000 vaccinated children and unvaccinated contacts.

- Inactivated poliovirus vaccine is injected intramuscularly and does not carry any risk of VAPP. The disadvantage is that it does not confer intestinal immunity.

- In recent decades, European countries have gradually shifted from OPV to IPV and today all EU/EEA Member States use IPV in their childhood immunisation programmes. The vaccine is applied as a combination vaccine, together with other vaccines. The number and timing of the doses in the primary series differs among EU/EEA Member States and the recommendations for individual countries can be reviewed in the ECDC’s Vaccine Scheduler.

- AFP surveillance is the gold standard for detecting polio cases and essential for global polio eradication. This includes case finding, sample collection, laboratory analysis and mapping of the virus to determine the origin of the virus strain. To ensure sensitivity of surveillance, at least one case of non-polio AFP should be detected annually per 100 000 population aged below 15 years. In endemic regions, to ensure even higher sensitivity, this rate should be two per 100 000.

- The examination of composite human faecal samples through environmental surveillance links poliovirus isolates from unknown individuals to populations served by the wastewater system. Testing for WPV and VDPV in sewage water can provide valuable supplementary information, particularly in urban populations where AFP surveillance is absent or questionable, persistent virus circulation is suspected, or frequent virus re-introduction has been identified (see WHO guidelines). Several Member States in the WHO European Region have enhanced their poliovirus surveillance by introducing enterovirus and environmental surveillance.

- The European Regional Commission for Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication (RCC) requests an annual progress report (details of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), environmental surveillance microbiological data, routine immunisation coverage, presence of high-risk groups or pockets of susceptible individuals and existence of a preparedness plan) from each Member State of the WHO European Region. It also reports on the status of global polio eradication, efforts to sustain polio-free status in the European Region and the conclusions of risk assessments and required risk mitigation measures.

Management and treatment

- All cases of AFP should be investigated for poliomyelitis.

- There is no specific treatment available for acute poliomyelitis and cases are managed supportively and symptomatically.

- Even a single case of poliomyelitis is considered an outbreak and requires urgent action. Under the International Health Regulations 2005 (IHR) any detection of poliovirus, whether WPV, VDPV (type 1, 2, or 3), or Sabin* type 2 virus more than four months after use of monovalent oral type 2 polio vaccine (mOPV2), must be assessed within 48 hours and then notified to WHO within 24 hours. The standard operating procedures (‘Responding to a poliovirus outbreak’) are provided by the Polio Global Eradication Initiative.

Note: The information contained in this fact sheet is intended as general information and should not be used as a substitute for the individual expertise of healthcare professionals.

*The so-called Sabin type 2 virus is the type 2 live-attenuated vaccine strain of poliovirus.