Effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination: Generic study protocols for retrospective case control and cohort studies based on computerised databases

In Europe, routine rotavirus vaccination of infants at the national level has been introduced with one or two vaccine brands in Finland, Austria, Luxembourg and Belgium within well-baby clinics or administered by general practitioners and paediatricians. When introducing a new vaccine, it is crucial to conduct studies evaluating the vaccination’s impact and effectiveness in order to decide on recommendations for its future use. ECDC has produced three generic protocols: a protocol for developing cohort studies to assess the effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccination in EU Members States; a protocol proposing prospective case control study designs to estimate rotavirus vaccine effectiveness; and a protocol for developing studies to assess the impact of rotavirus vaccination EU Member States.

Executive summary

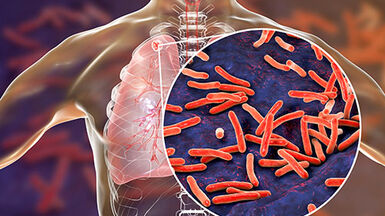

Rotavirus is the most common cause of gastroenteritis in children worldwide. It has been estimated that by the age of five years, nearly every child in the world has been infected with rotavirus at least once.

In April 2009, the World Health Organization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) recommended rotavirus vaccine for all children. In Europe, routine rotavirus vaccination of infants at the national level has been introduced in Austria, Belgium, Finland and Luxembourg. When introducing a new vaccine, it is crucial to conduct studies evaluating the vaccination’s impact and effectiveness in order to decide on recommendations for its future use. To this end, ECDC has produced three generic protocols: a protocol for developing cohort studies to assess the effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccination in EU Members States; a protocol proposing prospective case control study designs to estimate rotavirus vaccine effectiveness; and a protocol for developing studies to assess the impact of rotavirus vaccination EU Member States.

In this risk assessment, identifies the risk of infection for users of the kits unaware of the contamination with pathogenic agent as low, as the manipulation of the kit does not involve percutaneous injury-prone manipulations. However, infection resulting from the contamination of broken skin or mucous membranes may occur, even though the kit recommends and provides disposable gloves. The contribution of the kit to antimicrobial resistance in the EU/EEA population and environment is marginal.

As a result of this contamination event, German authorities have banned the importation of the kit. National competent authorities in the EU should review the authorisation of this commercial DIY Kit (CRISPR-Cas 9) product, or similar ‘citizen science’ biomaterials containing risk group 1 biological agents to produce genetically modified micro-organisms for educational or recreational purposes on the basis of the applicable European and national legislation.

Member States may also encourage consumers of such kits to purchase them from companies that have implemented quality control procedures and that follow proper packaging, labelling, and documentation requirements for transport of biological materials, such as stated in the WHO ‘Guidance on regulations for the Transport of Infectious Substances’.

At this stage, it is estimated that the distribution of such contaminated kits is very limited. The assessment of the risk associated with the DIY kits should be revised should further information indicate that the distribution of the kit extends more widely across the EU