Epidemiological update - Increase in Echovirus 30 detections in Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, July 2018

Since the beginning of the year, certain EU/EEA public health institutes have observed an upsurge in the number of positive enterovirus detections, especially Echovirus 30 (E30) cases. Norway [1] and the Netherlands [2] have published a report from national public health institutes on the increased E30 detections.

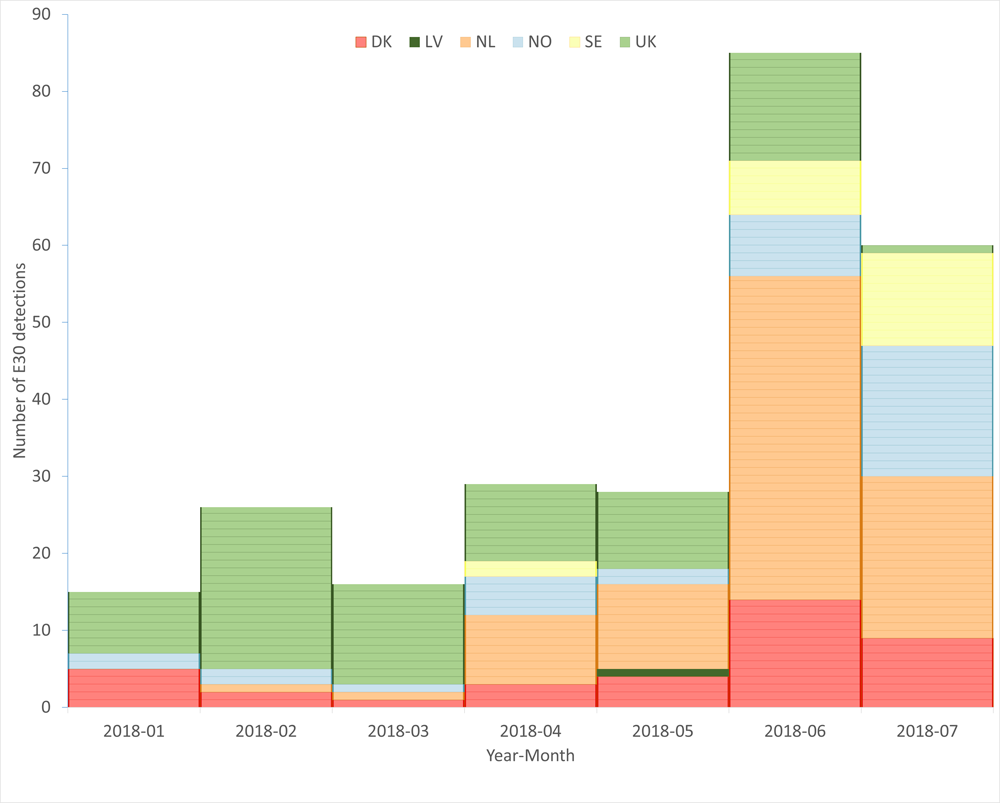

ECDC has compared the available E30 reports from nine Member States in response to a data call through the Epidemic Intelligence Information System–Vaccine Preventable Diseases (EPIS-VPD) platform to earlier collected country-specific E30 detection data from 2015 to 2017. Based on available preliminary data, 259 E30 detections from Denmark (38), Latvia (1), the Netherlands (85), Norway (37), Sweden (21) and the United Kingdom (England and Scotland; 77) were reported since the beginning of 2018 (Figure). An increase was observed in reports from the United Kingdom in February and in Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden in June 2018, with the Netherlands reporting higher numbers of E30 infections than previous years. Denmark reported that 23 out of their 38 E30 detections (61%) were from cerebrospinal fluid specimens, which can be used as a proxy for severe infection. In total, 149 out of 167 patients (89%) were reported with central nervous system symptoms from the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom. Of those, 27 were reported with meningitis, 26 encephalitis/meningitis and one patient with sepsis, fever, tachycardia and groaning respiration. For others, the specific symptoms were unknown. Until now, the epidemic has affected mostly infants 0-3 months old (22%) and 26-45-year-olds (38%). With the available preliminary data, the male to female ratio was 1.27.

E30 is a non-polio enterovirus that causes aseptic meningitis outbreaks worldwide. Such outbreaks have been detected earlier in Europe [3–10] and occur usually at five- to six-year intervals [11]. At the moment, the exact transmission route of current infections is unknown. However, non-polio enteroviruses transmit usually through faecal-oral or oral-oral routes. Unfortunately, specific prevention or control measures are not available for E30 and symptomatic treatment should be applied. High hygienic practices such as frequent hand washing, avoidance of shared utensils, bottles or glasses and disinfection of contaminated surfaces (e.g. with diluted bleach solution) are recommended to prevent the spread of E30 from person to person. In affected countries, further transmission of E30 cannot be excluded and therefore all EU/EEA Member States should remain vigilant for an E30 epidemic. Where relevant, national public health authorities should consider informing clinicians of increased numbers of aseptic meningitis related to E30 infection and of the importance of collecting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens even if white blood cell count is normal as well as adhering to recommendations on detection of non-polio enteroviruses in laboratories [12].

Data are preliminary and incomplete for July.

Member State contributors:

Birgit Prochazka (National Polio Reference Laboratory/AGES, Vienna, Austria), Katerina Fabianova (NIPH Prague, Czech Republic), Sofie Midgley and Thea Kølsen Fischer (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark), Jelena Storozenko (Riga East University Hospital, Latvian Centre of Infectious Diseases, National Microbiology Reference Laboratory, Latvia), Kimberley Benschop (on behalf of VIRO-TypeNed, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, the Netherlands), (Eric Claas (Leiden University Medical Center), Bert Niesters (University Medical Center Groningen), Jaco Verweij (Elisabeth Ziekenhuis), Katja Wolthers (VU University Medical Center Amsterdam), Suzan Pas (Microvida), Sylvia Bruisten (Amsterdam Municipal Health Center), Rob Schuurman (University Medical Center Utrecht), Richard Molenkamp (Erasmus University Medical Center), Lieuwe Roorda (Maasstad Ziekenhuis), Susanne Gjeruldsen Dudman (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norway), Katherina Zakikhany (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Sweden), Natasa Berginc (National Laboratory of Health, Environment and Food - Laboratory for Public Health Virology, Slovenia), Richard Pebody and Jake Dunning (Public Health England, the United Kingdom) and Alison Smith-Palmer (Health Protection Scotland, the United Kingdom).

References:

1. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Økning av enterovirus-infeksjoner i juni [Internet]. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2018 [accessed 3 Aug 2018].

2. Microvida – Medische Microbiologie West-Brabant en Zeeland. Start van het enterovirus seizoen [Internet]. . Breda: Microvida; 2018 [accessed 3 Aug 2018].

3. Trallero G, Avellon A, Otero A, De Miguel T, Perez C, Rabella N, et al. Enteroviruses in Spain over the decade 1998-2007: Virological and epidemiological studies. J Clin Virol. 2010;47(2):170-6.

4. Leveque N, Jacques J, Renois F, Antona D, Abely M, Chomel JJ, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Echovirus 30 isolated during the 2005 outbreak in France reveals existence of multiple lineages and suggests frequent recombination events. J Clin Virol. 2010;48(2):137-41.

5. Rudolph H, Prieto Dernbach R, Walka M, Rey-Hinterkopf P, Melichar V, Muschiol E, et al. Comparison of clinical and laboratory characteristics during two major paediatric meningitis outbreaks of echovirus 30 and other non-polio enteroviruses in Germany in 2008 and 2013. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(9):1651-60.

6. Savolainen-Kopra C, Paananen A, Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Simonen ML, Lappalainen M, et al. A large Finnish echovirus 30 outbreak was preceded by silent circulation of the same genotype. Virus Genes. 2011;42(1):28-36.

7. Perevoscikovs J, Brila A, Firstova L, Komarova T, Lucenko I, Osmjana J, et al. Ongoing outbreak of aseptic meningitis in South-Eastern Latvia, June - August 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(32).

8. Cosic G, Duric P, Milosevic V, Dekic J, Canak G, Turkulov V. Ongoing outbreak of aseptic meningitis associated with echovirus type 30 in the City of Novi Sad, Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, Serbia, June - July 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(32).

9. Mantadakis E, Pogka V, Voulgari-Kokota A, Tsouvala E, Emmanouil M, Kremastinou J, et al. Echovirus 30 outbreak associated with a high meningitis attack rate in Thrace, Greece. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(8):914-6.

10. Nougairede A, Bessaud M, Thiberville SD, Piorkowski G, Ninove L, Zandotti C, et al. Widespread circulation of a new echovirus 30 variant causing aseptic meningitis and non-specific viral illness, South-East France, 2013. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(1):118-24.

11. McWilliam Leitch EC, Cabrerizo M, Cardosa J, Harvala H, Ivanova OE, Kroes AC, et al. Evolutionary dynamics and temporal/geographical correlates of recombination in the human enterovirus echovirus types 9, 11, and 30. J Virol. 2010;84(18):9292-300.

12. Harvala H, Broberg E, Benschop K, Berginc N, Ladhani S, Susi P, et al. Recommendations for enterovirus diagnostics and characterisation within and beyond Europe. J Clin Virol. 2018;101:11-7.