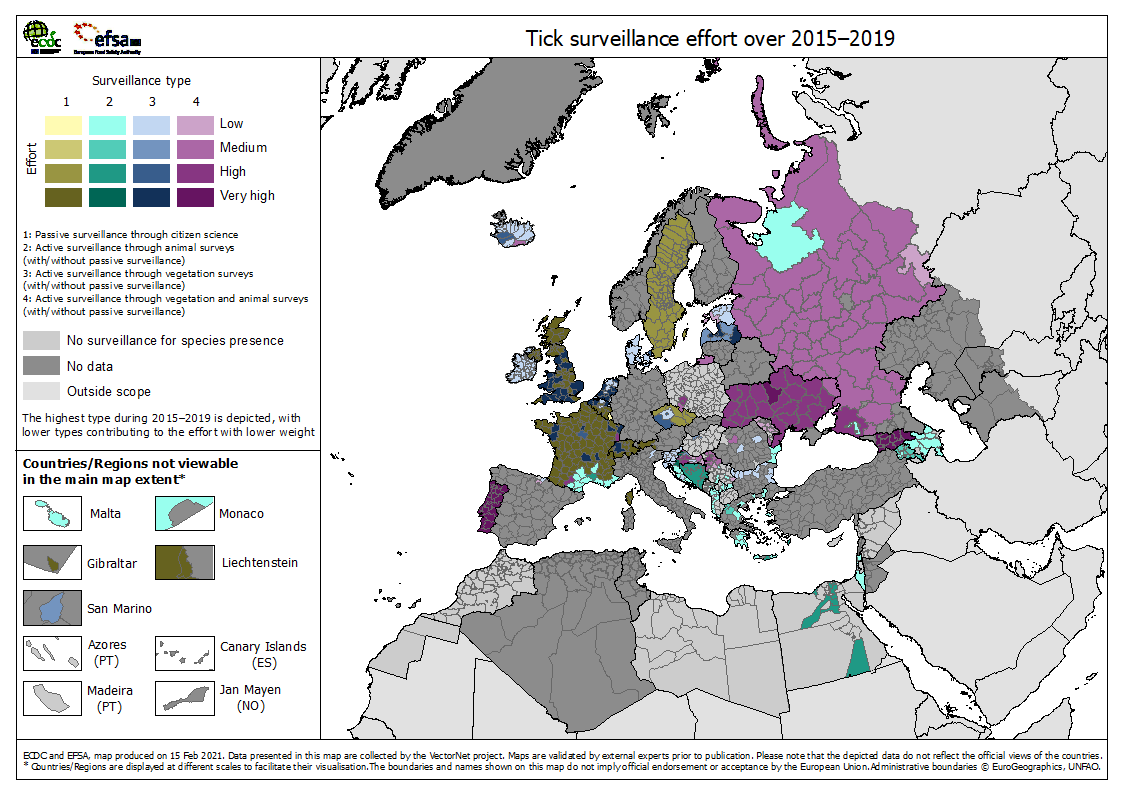

Tick surveillance effort over 2015–2019

The map Tick surveillance effort over 2015–2019' shows the surveillance effort per administrative area, by highest surveillance type.

Download

The surveillance categories are:

1 = passive surveillance through citizen science

2 = active surveillance through animal surveys (with/without passive surveillance)

3= active surveillance through vegetation surveys (with/without passive surveillance)

4= active surveillance through vegetation AND animal surveys (with/without passive surveillance)

The highest surveillance type that occurred in an administrative area during 2015–2019 is depicted, with lower type categories contributing to the effort score with a lower weight. Weights were as follows:

Table: Weights for tick surveillance effort

|

|

Highest level |

|||

|

Level |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

1 |

0.5 |

|

3 |

|

|

1 |

0.5 |

|

4 |

|

|

|

1 |

The data (occurrence of any surveillance activity type during the time period in the administrative unit) was collected by year over 2015 and 2016, and by month over 2017, 2018 and 2019 (The years 2015 and 2016 each carrying 1/12th of the weight of the later years). The score was summed and divided by the maximum score (38) and distributed over the four Effort classes (Low, Medium, High and Very high) according to equal intervals.

Tick surveillance methodology is variable, ranging from citizen science methods in the north and west of Europe, to the more intensive vegetation and animal monitoring in the eastern countries and in Portugal. Though data from some major countries remains to be entered, it is already clear that tick surveillance is very widespread but that the surveillance effort employed tends towards the lower end of the recorded spectrum.

The main activity for surveillance across Europe relates to the main risks posed by Ixodes ricinus and Lyme/tick borne encephalitis or Hyalomma marginatum and Congo Crimean Haemorrhagic Fever. This is reflected in the distribution map data. For example, there is good surveillance data for north-western Europe including some of the Nordic countries. There are data gaps for some of the larger countries of central, northern and western Europe, where the available distribution data suggests that surveillance does take place. Tick surveillance activity is good in eastern Europe and Caucasus where Hyalomma-associated risks are more common. Surveillance activity in the Balkans is good for some countries, whilst in others there are no data or only local/regional surveillance.

During the 2014–2018 Vectornet project cycle, there was a great deal of activity in establishing new tick surveillance in the Balkans, Caucasus and Northern Europe and this is reflected in the maps of tick surveillance activity. There is very little surveillance reported in North Africa even though there are public and veterinary tick-associated risks. This is reflected in the poor tick distribution data.

These patterns suggest that for ticks, priority for improved surveillance activities are in North Africa, the Balkans and parts of eastern Europe. Priority for collating data on surveillance where distribution data exist are the in countries that have yet to supply data.

Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and European Food Safety Authority. Tick maps [internet]. Stockholm: ECDC; 2021. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/surveillance-and-disease-data…