Diphtheria caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae ST574 in the EU/EEA, 2025

Genomic and epidemiological data available indicate local transmission in Europe among people experiencing homelessness, people who use or inject drugs, people who have not been vaccinated against diphtheria and older adults. These signals point to a wider circulation of C. diphtheriae ST574 across Europe.

Epidemiological situation

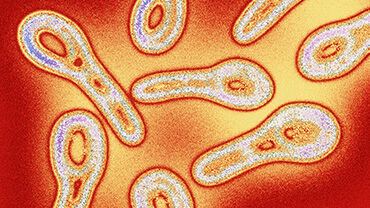

Diphtheria is considered to be a rare bacterial disease in Europe. Vaccination has considerably reduced the number of cases worldwide since the 1950s, thanks to mass immunisation efforts with a safe and effective vaccine.

Following an infection, people who have not been vaccinated against diphtheria may present with skin infections (cutaneous diphtheria), classical respiratory diphtheria and in rare cases, systemic diphtheria. In highly vaccinated populations, most infections are asymptomatic or mild. Case fatality for respiratory diphtheria can be as high as 5−10%.

Between 2009 and 2020, an annual average of 21 confirmed cases of diphtheria caused by toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae (C. diphtheriae) were reported across the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA). In 2022, 320 cases (318 confirmed and two probable) were reported. Epidemiological investigations concluded that this increase was due to an outbreak of diphtheria caused by C. diphtheriae, mainly linked to migrants who had been exposed to diphtheria during migration to Europe rather than importations from countries where diphtheria remains endemic. Most cases were associated with three sequence types: ST377, ST384 and ST574.

By late 2022, rapid response measures had helped to mitigate the outbreak and the overall number of reported diphtheria cases in the EU/EEA has been steadily declining since then. However, recent data indicate that C. diphtheriae ST574 continued to circulate after 2022 in at least five EU/EEA countries and in Switzerland. It was noted that a significant proportion of these cases occurred in populations vulnerable to infection. Between 2023 and 2025, EU/EEA countries reported 82 cases caused by C. diphtheriae ST574 to ECDC. Of these, at least 25 were in individuals from vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness, people who use or inject drugs, unvaccinated individuals, and older adults.

Genomic and epidemiological data available indicate local transmission in Europe among people experiencing homelessness, people who use or inject drugs, people who have not been vaccinated against diphtheria and older adults. These signals point to a wider circulation of C. diphtheriae ST574 across Europe. Given these findings, ECDC is making an assessment of the risk posed by C. diphtheriae ST574 disease acquired in the EU/EEA.

Risk assessment

Most EU/EEA countries have very high vaccination coverage for the primary course of diphtheria-containing vaccines. In the countries with high vaccination coverage, the risk to the general population is assessed as very low, but there could be sporadic cases among groups more vulnerable to infection and pockets of unvaccinated individuals owing to possible increased circulation of C. diphtheriae ST574.

Recommendations

- Increase awareness of diphtheria among healthcare workers, other professional caregivers, and volunteers in contact with populations more vulnerable to infection, such as recently arrived migrants, people experiencing homelessness or individuals residing, working or volunteering in transitional housing centres, and people who use or inject drugs. This includes providing information to facilitate recognition of its different forms (including cutaneous diphtheria), diagnosis and care. Furthermore, possible cases should also be isolated pending diagnostic confirmation, in accordance with national guidelines. Clinicians should be made aware of the need to consider diphtheria in the differential diagnosis of patients with a compatible clinical presentation.

- Implement health promotion activities and promote engagement with populations more vulnerable to infection. Ensure that public health measures are in place, including outbreak response, that follow ethical guidelines, safeguard individuals' rights, and minimise the risk of stigmatisation and marginalisation.

- Promote and monitor equity of access to immunisation. This particularly applies to populations more vulnerable to infection and groups at risk of being socially marginalised, such as migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers, but also disadvantaged populations (e.g. individuals living with alcohol use disorder, those who use or inject drugs, or people experiencing homelessness). Vaccination against priority diseases, such as diphtheria, poliomyelitis and measles, which are particularly prone to spreading in crowded areas, should be offered promptly, in the absence of documentation of prior vaccination. If a larger outreach is required, opportunities for broader vaccination efforts should be based on the risk profile of the group (e.g. hepatitis B).

- While prioritising immunisation to prevent disease, regularly assess the level of access to diphtheria antitoxin (DAT) and, in the context of global DAT shortages, where necessary, consider cross-border options to secure rapid access for all patients with suspected or confirmed diphtheria-toxin-induced disease.

- Conduct enhanced surveillance, including the use of molecular typing and whole genome sequencing (WGS) to confirm potential epidemiological links between cases (when relevant, and in particular in the case of potential cross-border events), to investigate the genetic determinants involved in unusual AMR patterns, and to analyse shifts in epidemiology (e.g. increases in case numbers at national or international level, involvement of atypical population groups).

Download

Read the news item

Press release

Protecting the most vulnerable: ECDC recommendations to address the ongoing local transmission of diphtheria

Diphtheria remains a public health concern in Europe, prompting ECDC to recommend targeted measures to protect vulnerable populations.