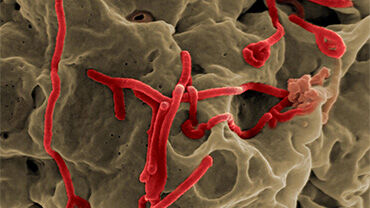

Rapid Risk Assessment: Risk of Sudan virus to EU/EEA citizens considered very low

In this Rapid Risk Assessment, ECDC assesses the risk of Ebola disease caused by Sudan virus, which is one of the human ebolaviruses, as very low to citizens in the EU/EEA.

An outbreak was declared in Uganda on 20 September 2022, caused by the Sudan virus. As of 5 November 2022, Uganda has experienced 132 confirmed cases of Ebola disease caused by Sudan virus, including 53 deaths and 61 recoveries across eight districts.

The current outbreak is the first outbreak of Sudan virus disease in Uganda since 2012. With seven previous outbreaks since 2000, Uganda has experience in responding to outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus. Necessary actions in response to the current outbreak have been initiated quickly.

The probability of exposure to Sudan virus of EU/EEA citizens living and travelling in the affected areas in Uganda is very low, provided they adhere to the recommended precautionary measures. Although infection with Sudan virus leads to severe disease, the impact at population level for EU/EEA citizens living and travelling in the affected areas in Uganda is deemed to be low. Therefore, the current overall risk for EU/EEA citizens living and travelling to the affected areas in Uganda is considered low.

The likelihood of importation and secondary transmission of Sudan virus within the EU/EEA is very low as cases are likely to be promptly identified and isolated, and follow-up control measures are likely to be implemented. Overall, the current risk for citizens living in the EU/EEA is considered very low.

Executive Summary

Since the beginning of the outbreak declared on 20 September 2022 and as of 5 November 2022, Uganda has experienced 132 confirmed cases of Ebola disease (EBOD) caused by Sudan virus (SUDV), including 53 deaths and 61 recoveries across eight districts (Bunyangabu, Kagadi, Kampala, Kassanda, Kyegegwa, Masaka, Mubende and Wakiso). Mubende and Kassanda districts have been the most heavily affected so far. The capital city, Kampala, reported its first case on 21 October 2022 and since then 18 cases have been detected. There have been 18 cases of infection among healthcare workers including seven deaths. The overall case fatality rate as of 5 November 2022 is 40% among confirmed cases. An additional 21 deaths have been classified as ‘probable cases’ among individuals who died before a sample could be obtained.

The current outbreak is the first outbreak of Sudan virus disease (SVD) in Uganda since 2012. With seven previous outbreaks since 2000, Uganda has experience in responding to outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus and SUDV, and necessary actions in response to the current outbreak have been initiated quickly. The Ugandan Ministry of Health (MoH) has activated a national response plan to guide outbreak preparedness and response operations. Epidemiological investigations, community-based surveillance, active case finding and contact tracing are ongoing in all the affected districts. Laboratory testing is in place and efforts are being made to scale up the deployment of additional mobile laboratories to affected districts. Emergency medical teams, isolation centres, and treatment units to support case management have been established. In addition, the MoH is supporting safe and dignified burials in all high-risk districts.

In the absence of licensed vaccines and therapeutics for the prevention and treatment of SVD and considering the geographical expansion of the SVD outbreak to urban settings, the World Health Organization (WHO) assessed the current risk to be very high at the national level, high at the regional level and low at the global level.

The WHO has initiated consultations with vaccine developers to identify candidate vaccines against SUDV with potential to be tested through randomised clinical studies in Uganda. At present, three candidate vaccines are under consideration and reviews of the clinical study protocols by ethical and regulatory committees in Uganda are currently underway.

The probability of exposure to SUDV of EU/EEA citizens living and travelling in the affected areas in Uganda is very low, provided they adhere to the recommended precautionary measures. Although infection with SUDV leads to severe disease at individual level, the impact for the EU/EEA citizens living and travelling in the affected areas in Uganda considered at a population level is deemed to be low. Therefore, overall, the current risk for EU/EEA citizens living and travelling to the affected areas in Uganda is considered low.

The likelihood of importation and secondary transmission of SUDV within the EU/EEA is very low as cases are likely to be promptly identified and isolated, and follow-up control measures are likely to be implemented. During the West Africa EBOD outbreak in 2013–2016, which was the largest EBOD outbreak to date, where tens of thousands of cases were reported, with transmission in large urban centres, and hundreds of EU/EEA humanitarian and military personnel deployed to the affected areas, there were eight imported cases to the EU/EEA (Italy, Spain) and the United Kingdom.

Overall, the current risk for the citizens in the EU/EEA is considered very low.

Options for response

In order to ensure, and if necessary, strengthen the preparedness and response capabilities, EU/EEA countries should consider reviewing the standard operating procedures (SOP) on isolation and treatment for EBOD cases, and on contact tracing and quarantine for contacts of cases. EU/EEA public health authorities should prioritise the following preparedness activities in view of the ongoing outbreak in Uganda:

- Increasing awareness among visitors to, and residents in affected areas, as well as returning travellers;

- Awareness activities for health professionals including awareness of the outbreak, clinical suspicion for imported cases, infection prevention and control (IPC) procedures and management of suspected or confirmed cases;

- Reviewing testing capacity and procedures, particularly as regards SUDV (most EU/EEA countries have the laboratory capability to perform ebolavirus diagnostic testing);

- Risk communication activities for the public.

Awareness activities for healthcare providers in the EU/EEA should include informing of and sensitising to:

- The possibility of SVD among travellers returning from affected areas;

- The clinical presentation of the disease and the need to enquire about the travel history and contacts of people returning from countries experiencing SVD outbreaks;

- The availability of protocols for testing possible cases and procedures for referral to healthcare facilities;

- The imperative need for strict implementation of IPC measures when providing care to patients with suspected or confirmed SVD, such as the use of personal protective measures and equipment, disinfection procedures in accordance with specific guidelines and WHO infection-control recommendations.

EU/EEA visitors and residents in affected areas in Uganda should follow the recommendations of the local health authorities on SVD prevention and control, and apply the following precautionary measures:

- Avoid contact with symptomatic patients/their bodily fluids, bodies and/or bodily fluids from deceased patients;

- Avoid consumption of bushmeat and contact with wild animals, both alive and dead;

- Wash and peel fruits and vegetables before consumption;

- Wash hands regularly using soap or antiseptics hand-rub formulations;

- Ensure safe sexual practices.

ECDC considers that travel restrictions, which usually have an adverse impact on the affected country’s supply chains, as well as screening of travellers returning from Uganda would not be an effective or cost-effective measure to prevent introduction in the EU/EEA. Screening of incoming travellers is time and resource consuming and will not efficiently identify infected cases. Instead, both experience and evidence show that exit screening from affected countries can be more effective to support the containment of the disease spread. It should be noted that the positive predictive value of the detection of one individual with an SVD infection through exit screening is nevertheless rather low.

Download